Our History and Timeline

From 1973 to 2023: 50 Years of Task Force Activism, Advocacy, and Organizing for LGBTQ Liberation

We are the activists who drive the LGBTQ movement forward. We are the organizers who sustain the hard-won progress. We show up at the protests and celebrations. You’ll find us at marches and committee hearings by day and on the dance floor by night.

We are the National LGBTQ Task Force, the country’s oldest national LGBTQ rights organization.

Our history illustrates the decades of effort led by our organizers, who used their knowledge, passion, and energy to lay the groundwork for the LGBTQ rights movement of the 21st century. Our history tells our story and shapes our vision for the future—to build a bold, inclusive, and intersectional world where everyone is free to be their authentic self.

NYC LGBTQ History Project

NYC LGBTQ History ProjectOctober 1973

Queer Activists Establish the National Gay Task Force in New York City

The National LGBTQ Task Force was founded in October 1973 in New York City by several activists who saw a need for a powerful, unified, and organized voice in the burgeoning gay rights movements. Established by several leaders involved in post-Stonewall queer activism, including Dr. Bruce Voeller, Barbara Gittings, Frank Kameny, Dr. Howard Brown, Arthur Bell, Ron Gold, Nathalie Rockhill, and Martin Duberman, the Task Force became the first national LGBTQ rights organization in the United States. The Task Force founders later became prominent and consequential leaders throughout the 20th century gay rights movement.

December 1973

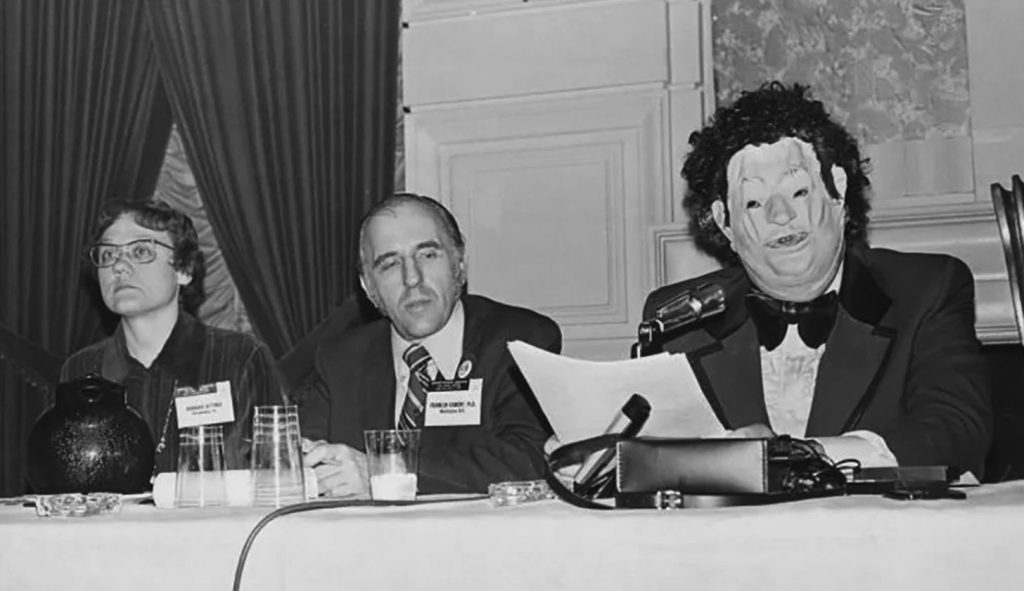

Task Force Activists Remove “Homosexuality” from the DSM

Only a few months after the Task Force’s founding, we achieved our first major victory–getting homosexuality removed from the American Psychiatric Association’s list of mental disorders. The victory was the first major step in destigmatizing queerness and played a crucial role in moving the American public towards greater acceptance of LGBTQ people.

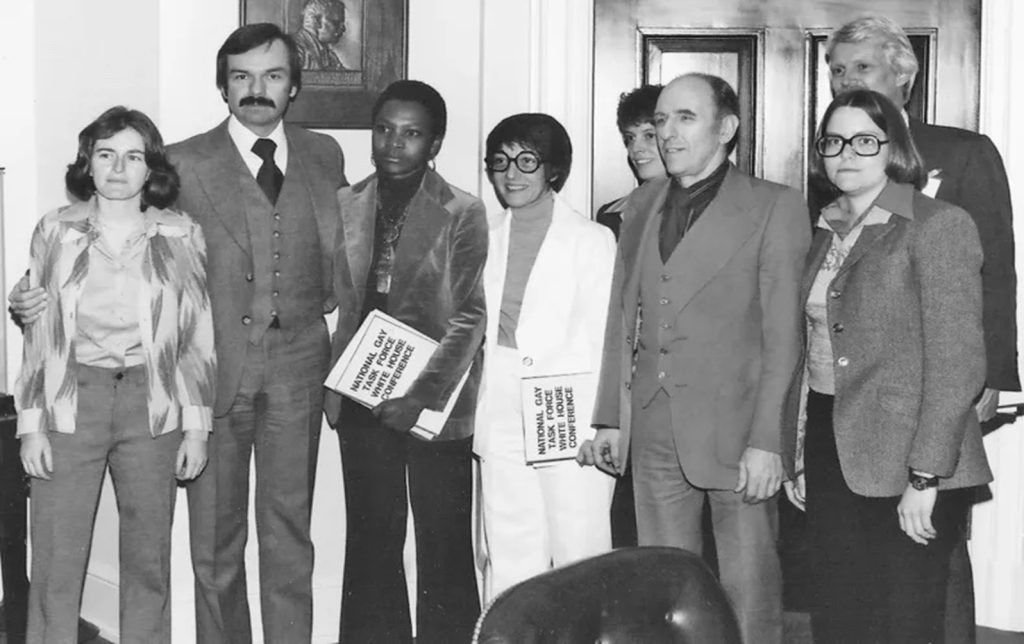

March 1977

The First Time in American History Queer Activists met with the White House to Discuss Gay Rights

Jean O’Leary, then co-executive director of the Task Force, arranged a historic White House meeting with representatives of several gay organizations with Midge Costanza, Assistant to the President for Public Liaison President Jimmy Carter. This is the first time in American history queer activists met with the White House to discuss gay rights.

1983

Virginia Apuzzo Testifies in Congress About the Lack of a Federal Response to AIDS

Task Force co-founder and biologist Dr. Bruce Voeller leads efforts to successfully change what the CDC referred to as GRID (Gay-related Immune Deficiency Disorder), to AIDS (Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome)

1984

Apuzzo Founds the AIDS Action Council

In the 1970s and 1980s, much of the world watched as HIV/AIDS devastated queer communities, leaving LGBTQ people to literally fight for their lives to access life-saving treatment and research. Throughout the epidemic, we played a pivotal role in demanding federal action. In 1984, then Executive Director Ginny Apuzzo founded the AIDS Action Council, the country’s first advocacy organization focusing on public policy and funding for AIDS research.

1985

Task Force Headquarters Move From New York City to Washington, DC

In 1985, Jeff Levi became the executive director of the Task Force, and we moved our headquarters from New York City to Washington, DC, cementing policy and political advocacy as a core part of Task Force activism. That year, we secured federal funding for community-based AIDS service organizations—for the first time since the start of the AIDS crisis.

Levi devoted the next four years of his tenure as executive director advocating for effective federal policy and funding for AIDS, and fighting homophobic legislation from policymakers. He founded the new coalition, National Organizations Responding to AIDS (NORA), which played a key role in pushing the government to define the AIDS epidemic as a public health emergency.

October 1987

The Task Force Organizes the Second March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights

We played a major role in organizing the 1987 March for Lesbian and Gay Rights March on Washington. More than 200,000 people attended to protest government inaction on the AIDS crisis and the Bowers v. Hardwick SCOTUS decision that upheld Georgia’s sodomy laws. ACT UP, the influential AIDS direct action organization, received national media attention for the first time and activists unveiled the National AIDS Memorial Quilt.

1988

The Task Force hosts the first Creating Change Conference in Washington, D.C.

The Creating Change Conference grew out of a need for organizers throughout the LGBTQ movement to come together to collaborate, learn from one another, and strategize the future of the movement. Held annually since 1988, the Creating Change Conference has grown to become the largest annual gathering of LGBT activists, organizers, and advocates in the country, training thousands of organizers who used their knowledge, passion, and energy to lay the groundwork of the LGBTQ rights movement of the 20th century.

1989

Advocating on Campuses and for Lesbian and Gay Families

The National Gay and Lesbian Task Force starts publishing a campus organizing newsletter and initiates the Lesbian and Gay Families Project to advocate for family diversity and acceptance.

April 1993

The Task Force is a Lead Organizer for the Third March on Washington for Lesbian, Gay, and Bi Equal Rights and Liberation

Focusing largely on President Bill Clinton’s failure to fulfill the promises he made to the queer community during his campaign, state bans on same-sex adoption, and AIDS, the march brought together hundreds of thousands of people committed to fighting for LGBTQ justice.

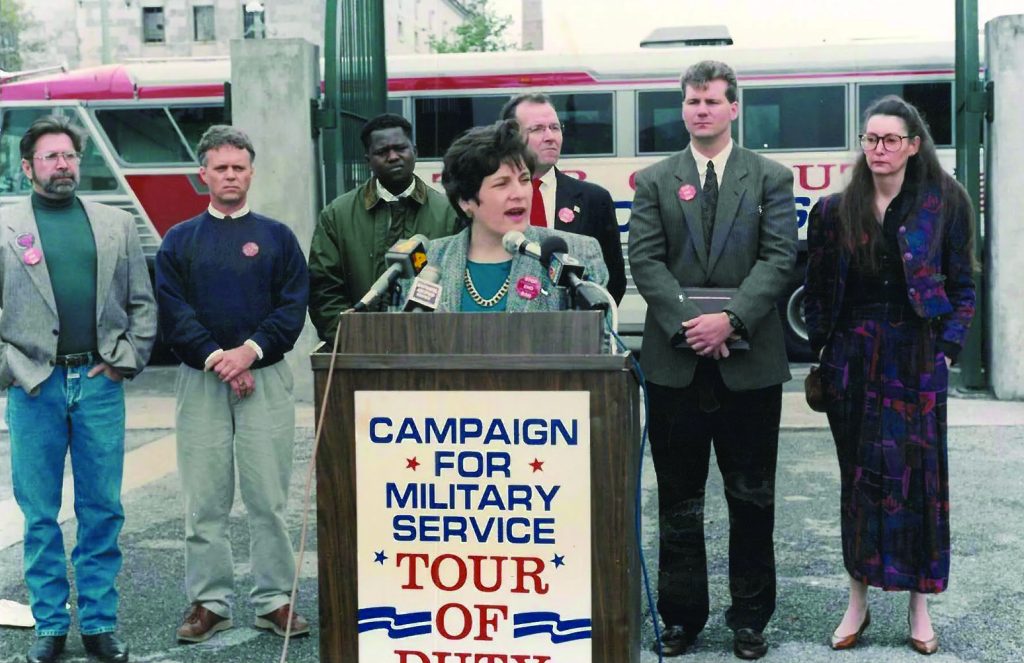

1993

The Task Force Founds the Military Freedom Project in partnership with the ACLU

The effort was led by Tanya Domi, veteran and director of the Military Freedom Project. In May, Domi testified in front of the House Armed Services Committee about lifting the ban on LGBTQ service members and traveled the country with other veterans to advocate for queer inclusion in the military.

1995

The Task Force establishes the Task Force Policy Institute.

Among its first publications are the Campus Organizing Manual for LGBTQ college students and the Marriage Organizing Kit to guide organizers and activists across the country. It also released the first annual survey of state legislation related to LGBTQ issues: Capital Gains and Losses: A State-by-State Review of Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender, and HIV/AIDS-Related Legislation.

1996

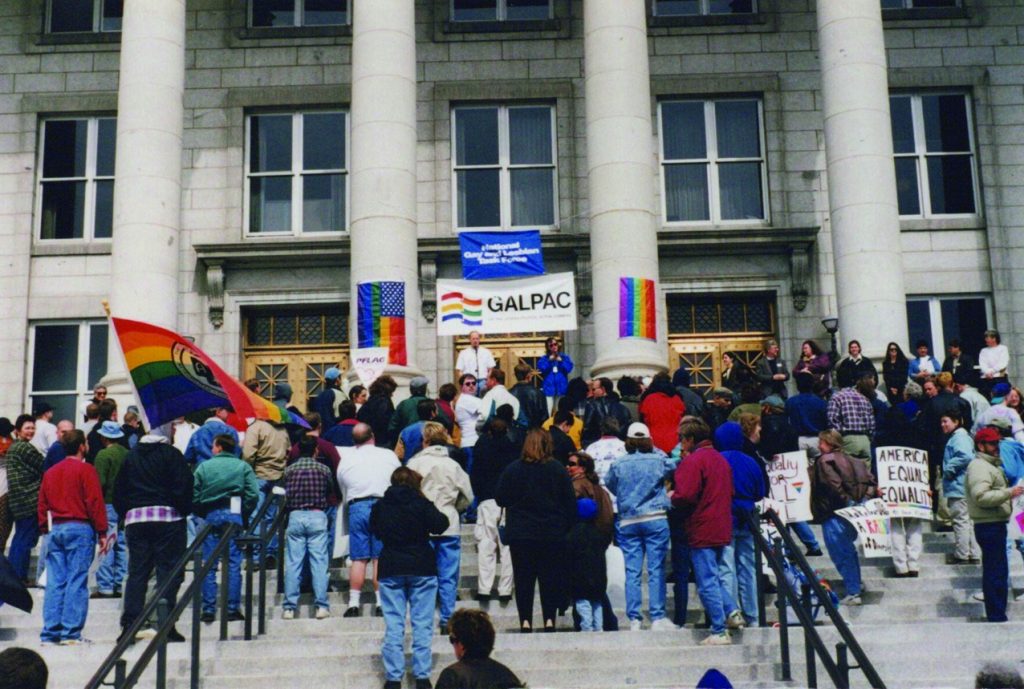

The Task Force Launches the Equality Begins at Home Campaign

In 1966, we kicked off the Equality Begins at Home campaign, a nationwide initiative for LGBTQ rights at the state level. The campaign was a response to laws banning cities from providing health benefits to domestic partners of unmarried city workers, forbidding unmarried couples from adopting children, and rolling back funding for needle exchanges during the HIV/AIDS crisis.

2010

The Task Force launches the “Queer the Census” campaign

The Task Force launched the initiative to tally and count the LGBTQ community in the United States, with the understanding that census data is crucial to writing informed and relevant state and federal legislation.

2014

The Task Force Launches the Equality Begins at Home Campaign

Under executive director Rea Carey, the new name reaffirmed the Task Force’s commitment to intersectional activism and radical inclusion. The name explicitly integrates bisexual, transgender, and queer into the fabric of the organization. Along with the name change, the Task Force launched their new and current slogan, “Be You,” which speaks to the Task Force’s desire for everyone to be themselves in a more just, and liberated society.

“Now more than ever we have the power to define the future we want; a world where every LGBTQ person can be themselves without any barriers. We have worked hard for decades to create this momentum. Let’s seize this opportunity, let’s be ourselves fully, and let’s make a future together that’s worthy of our struggle.”

Rea Carey, Executive Director of The Task Force in 1994

2015

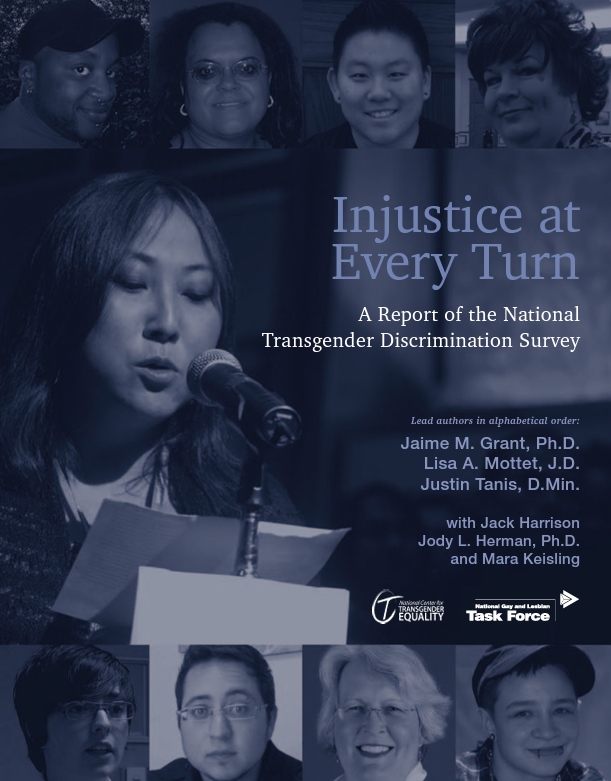

First National Transgender Discrimination Survey

The Task Force and the National Center for Transgender Equality release the first National Transgender Discrimination Survey, Injustice at Every Turn, which becomes a critical resource for the community, media, and researchers.

2020

The Task Force launches the Second Queer the Census Campaign

The campaign pivots to digital because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

2021

Kierra Johnson Named Executive Director

Kierra is the first Black woman to lead the Task Force. She became one of few queer-identified women of color at the helm of a national LGBTQ organization. She is recognized as a national expert on queer and reproductive rights issues, and has testified in front of the U.S. House of Representatives and has appeared in Newsweek, The New York Times and NPR.

2022

The Task Force Launches the “Ban the Repro Binary” Campaign in the Wake of the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health

After the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, the Task Force reaffirmed its commitment to reproductive justice and bodily autonomy, recognizing that everyone has the right to decide whether or when to become a parent, parent the children they have, and to do with dignity and free from violence and discrimination.

The Task Force campaign encouraged people to look beyond the binary and understand that LGBTQ people need access to reproductive health care, including contraception, abortion, assisted reproductive services, HIV care, pregnancy care, parenting resources, and more.

Support Our Work